Using C++ will not automatically produce more efficient code.

Using Rust will not automatically produce more efficient code.

Using C will not automatically produce more efficient code.

Learning to use a debugger is a step towards producing efficient code.

Learning to use a profiler is a step toward producing efficient code.

Rust’s Ownership concept has been tried before. See FBP.[1]

I used ownership in the 1990’s, but called it “physical objects”. I didn’t write about it. Garbage Collection turned out to be more convenient.

Lisp uses Garbage Collection, but it is possible to craft a Lisp program that doesn’t need Garbage Collection during its steady state. Lisp allocates and GC’s memory when CONS is called. It is possible to write Lisp code that doesn’t invoke CONS.

Efficiency is a per-project concern and cannot, reasonably, be generalized.

Efficiency is the concern of Efficiency Engineering. Efficiency concerns should not pollute Architectural concerns.

MC6809 (an 8-bit processor) was more memory efficient than MC68000 (a 16-bit processor) code. I measured that 6809 code was 40% the size of 68000 code. I attributed the size difference to be due to the size of instructions – for the 6809, opcodes were bytes (8 bits), whereas for the 68000 opcodes were words (16 bits).

One of the early Burroughs processors used Huffman Encoding to encode instructions. The most common instruction was 2-bits long.

Smalltalk supported duck-typing with caches. Methods were first looked up dynamically, then cached. As the app ran and reached steady-state, the caches would tend towards containing the most-frequently-used methods, resulting in faster lookup for more-frequently-used methods. Obviously the caches were populated on a per-application basis. This was “good enough” and the compiler remained simple, not needing to predict the frequency-of-use for every method.

This method of optimization (caching) allowed the original Architecture to remain intact, while allowing Efficiency Engineers to make the result faster.

I view everything as an interpreter. The difference between compile-time and run-time is simply a function of the number of times each interpreter runs. It is generally expected that compile-time interpreters (“the compiler”) will be run much less frequently than the run-time interpreters (“the app”).

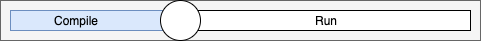

We can view this as a slider ...

Our division between compile-time and run-time is arbitrary.

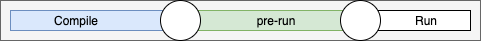

What if the slider had two knobs? Compile-time, pre-run-time, run-time?

What if we had an infinite number of knobs on the slider? What if, say, pre-run-time were divided up into smaller and smaller pieces, each with its own distinct purpose? The tenet of component-based design is to “do one thing, and do it well” in each phase. Could pre-run-time be broken down into method-lookup caching, branch-prediction, etc.?

The front-end, compile-time, would have to create an intermediate form (IR – internal representation) that was easily searched and re-arranged in a successive manner. I think of RTL[2] and OCG (Orthogonal Code Generator, Cordy)[3] technologies. Data Descriptors (Holt)[4] show a way to represent data locations in a generalized manner. FP (Functional Programming) leads to thinking about chains of filters.

O(N) analysis says that O(1) is “better” than O(3).

The real analysis is UX time. What performance does the user see? What performance does the user care about? What performance does the user not care about?

O(3) is OK in a Component, if the Component is small, from a user’s perspective.

How do the O(N)s in Components add up in UX? The answer used to be a no-brainer, when everything was done on one CPU. Now, a long time after O(N) analysis was invented, hardware is much cheaper, processors are much cheaper and memory is cheaper and more abundant.

We need to re-examine efficiency analysis in light of the new realities and, in light of FD.[5]

[1] https://jpaulm.github.io/fbp/index.html

[2] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220404697_The_Design_and_Application_of_a_Retargetable_Peephole_Optimizer

[3] https://books.google.ca/books/about/An_Orthogonal_Model_for_Code_Generation.html?id=X0OaMQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_descriptor

[5] Fractal Design