Type stacks

We can think in terms of stacks[1] of types.

Everything Starts Out as a Bit

Everything starts out as a bit.

Bits are Parsed Into Bytes

Fig. 1

Bits can be parsed into bytes.

The filter for such a parser is nearly trivial: collect 8 bits, emit a byte. Emit an error if you see an EOF[2] when you have collected fewer than 8 bits.

Even a filter as simple as that above can have more than one implementation.

Another implementation might pad 0’s onto the end of an unfinished byte, when an EOF is seen.

Or, we might pad 0’s at the front of the byte upon EOF.

Or, we might pad with trailing 1’s, or we might pad with leading 1’s.

Or, we might parse bits into ASCII and use the top bit as a parity bit.

Or, we might parse bits into EBCDIC.

Clearly, if we try to do all of the above in a single filter, the code will become unreadable and there will be option flags[3] (TL;DR). There will be too many flags. They will need to be documented and memorized.[4]

Bytes Parsed into More Interesting Structures

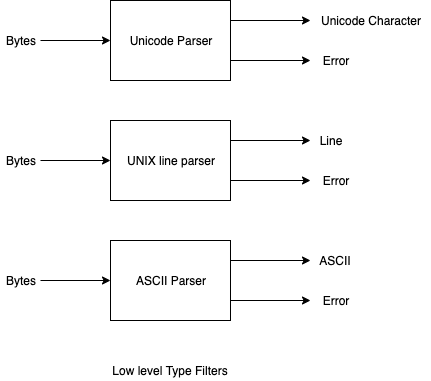

We, then, create a handful of filters. Some low-level filters are shown in Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Low Level Filters

(Filters can further be chained together to recognize more interesting, more complicated, types).

Composition

Note that it is hard(er) to implement filters as shown in Fig. 2 using only functions.

The boxes emit two kinds of objects (good output[5] and errors), but could emit many different kinds of objects. Functions return[6] only one object.

These boxes emit objects at various times. For example, the UNIX Line filter might need to wait for 80 bytes before seeing a line-feed[7]. It emits a full line only after it has seen all bytes that belong to that line. It waits and SENDs nothing until it has sees all 80[8] bytes. If the UNIX Line filter contains a buffer that overflows, it can emit an error[9] at a random time.

RATFOR, Software Tools

RATFOR[10] built line filters using Procedures and Functions. It used the Operating System to preempt filters.

Efficiency

We might prefer something that is more efficient than full-blown Operating Systems, to implement filters. Ideally, we want filters to be at least as efficient as function calls.

The concept of closures[11] is prevalent in modern languages.

I argue that closures are threads.

Operating system-level processes (threads) are threads that include provisions for time-sharing, full-preemption, memory sharing, etc. Most of these features are unnecessary[12] in most uses of threads. Most problems in multi-tasking can be ascribed to these, mostly unnecessary features. These complications are needed only by programs[13] such as Linux, Windows, MacOS, etc.

I argue that operating-system threads are ad-hoc closures, implemented in assembler.

[1] or “pipelines”, here “stack” is used in the way it is used to describe ethernet handlers

[2] We ignore how EOF is recognized, for simplicity. EOF might be another input, it might be a timeout, etc.

[3] a.k.a. parameters.

[4] Common Lisp format directive strings are like that. There are many, many options. One simply memorizes the subset of directives that one tends to use. Then, over time, one learns how to use new options, one at a time. The documentation is split into two major streams - a legalistic explanation of every option, and, a cookbook version that lists immediately useful patterns. Emacs is like that, also.

[5] Unicode, lines, ASCII

[6] Return is a subset of Send(). Return pre-assumes that every function will always produce a single output. Send() can be used multiple times to produce multiple outputs.

[7] \n

[8] In this example

[9] Of some kind.

[10] https://www.amazon.com/Software-Tools-Brian-W-Kernighan/dp/020103669X/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=ratfor&qid=1577201614&sr=8-1

[11] Anonymous functions, callbacks, futures, etc.

[12] accidental complexity

[13] libraries