Introduction

In this essay, I describe the very bare bones for implementing concurrency in any language.

I know that this can be implemented in JavaScript - I've done it and will blog about it in further essays. Incidentally, I've also built preliminary versions of this in Common Lisp, C, C++ and assembler. Variations of this technique have been put into production, in multiple projects)

Concurrency is very simple and its implementation should be "obvious". You might wish to skip over the details, once you get the hang of it.

Forget what you already know about multitasking and read on …

[The point of this essay is to show only the basics of this technique. I use hard-wired code for illustration. If a more fully-developed version of the code is desired, see my essays about HTML Components - ag-js-1, ag-js-2, and ag-js-3]

Diagram

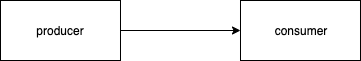

The most simple example of concurrency can be summed up in Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Basic Concurrency

Overview of Concurrency

Concurrency, at its most basic, is very simple.

A part is a black box with input pins and output pins.

A part can send events to another part. The event is pushed out of the first part's output pin and arrives at the other part's input pin. Events can only travel on wires.

A part contains a number of actions.

Every time an event arrives at the input pin of a part some action is triggered.

There are rules for how actions are triggered, but we'll skip that for now.

There are two kinds of parts:

- a leaf part

- a schematic

A schematic contains other parts and a set of wires (that connect the parts together).

In other words, a schematic can be broken down further into more parts.

A leaf part cannot be broken down any further. A leaf part contains actions which might (or might not) produce outputs on the output pins of the leaf part.

A schematic also contains actions, but those actions are composed of the actions of the parts contained in the schematic. We can keep breaking parts down until we hit bottom - i.e. a leaf part that does something. On the outside, looking in, we see parts as black boxes - we don't know (or care) whether a part is a leaf or if it is a schematic.

Implementing Concurrency

We can implement a simulation of concurrent parts in any programming language.

For this, we need some routines.

We need a dispatcher.

We need a way to transfer data between routines.

That's about it.

Present-day multitasking is inflicted with accidental complexity.[1] Multitasking seems to be difficult. I will describe something much simpler, but just as useful.

- Actions are functions with no user-defined parameters, no return values, no exceptions and no way to call other routines.

- A dispatcher is the only routine that can call other routines. Called routines always return to the dispatcher.

- We will transfer data using queues.

Example - JavaScript Implementation

In the following example, I will show how to build a simple system with two components and one dispatcher. I have used this same technique to build much larger systems (100s and 1,000s of components).

This example probably looks too simple and not complicated enough. It is an "overnight success" - it took me only 30 years to arrive at this conclusion.

The technique has been used to build distributed systems and has been put into production (several times).

[I don't recommend that components, queues and dispatchers be implemented as in this example. I am trying to be excruciatingly transparent.]

The example appears in the rest of this essay and can be found at < … >

Components - JavaScript

I wish to keep this essay very simple, so I will describe an example which contains only two components. One component Sends a string to the other component - the usual "Hello World".

I will name the components "sender()" and "receiver()".

In JavaScript, a part is a function that receives messages. [The function can use a switch statement (or an if-then-else) to examine the message's pin field, and decide which action to invoke. In this simple example, we won't bother with pins, we'll just assume that every part has one input pin and one output pin. We'll hard-code the wiring table in the JavaScript function that I call Send() (see section Send - JavaScript).

The component producer(), is:

function producer (message) {

send ("sender", "Hello World");

}

and the component consumer() is

function consumer (message) {

console.log (message);

}

Points to note:

- producer() does not call consumer() directly

- the action in the producer part consists of one line of JavaScript code (send (…))

- the action in the consumer part consists of one line of JavaScript code (console.log (…))

- the action code in producer does not bother to check the message - it just fires its result "Hello World" out of its output pin

- the action code of consumer doesn't bother to look at the incoming message, it just logs it (console.log (message))

- neither part, producer nor consumer, gets to define the parameter list, there is always one message parameter passed in to the action code.

Queues

Each component has a pair of private queues that can be accessed only by the send() an receive() routines.

[In Javascript, queues are implemented as arrays. An empty queue is []. A queue can hold mixed elements of any type.]

var sender_input_queue = [];

var receiver_input_queue = [];

Dispatcher - JavaScript

The dispatcher[2] invokes, arbitrarily, any routine that is ready to run.

A routine is ready to run if its input queue is non-empty.

function dispatcher () {

while (true) {

if (sender_input_queue.length > 0) {

var message = sender_input_queue.pop ();

sender (message);

} else if (receiver_input_queue.length > 0) {

var message = receiver_input_queue.pop ();

receiver (message);

}

}

}

Send - JavaScript

The send () function is:

function send (from, data) {

if (from == "sender") {

receiver_input_queue.push (data);

} else if (from == "receiver") {

sender_input_queue.push (data);

} else {

fail ();

}

}

[in this simple example, sender's output is always piped to receiver's input]

Startup

sender ();

Steady State

dispatcher ();

JS Code

node basic.js

see code in https://github.com/bmfbp/arrowgrams/blob/master/basic-concurrency/basic.js

Index.html

see https://github.com/bmfbp/arrowgrams/blob/master/basic-concurrency/index.html

load index.html in a browser, hit the "run" button

Benefits of Concurrency

I claim that concurrency addresses many issues, including:

- architectural flexibility

- scalability

- isolation

- namespaces

- type checking

- thread safety, fairness, and all that …

- synchronization

- asynchronous I/O

- box-and-arrow diagrams (that work)

- machine control instead of calculation

- readability

- expressiveness - DI (Design Intent)

- multiple use (augmented reuse)

- removal of exception syntactic sugar

- removal of parameter syntactic sugar

- remove of return value syntactic sugar

- layers, scoping

- easier scheduling

- better testabilty

- compartmentalization of development tasks

- etc.

but, I will not conflate this simple example with such issues. I will address these issues in other essays.

Call Return Spaghetti

see https://guitarvydas.github.io/2020/12/09/CALL-RETURN-Spaghetti.html

[1] I claim that the accidental complexity comes from premature optimization. Optimization was necessitated by the ground truth in 1950 - processors were very expensive, memory was expensive and very limited.

[2] In production, we would write the example code differently. Many optimizations present themselves, for example, we don't need to burn a hole in the processor using a while(true) loop.