Parsing Diagams - Containment

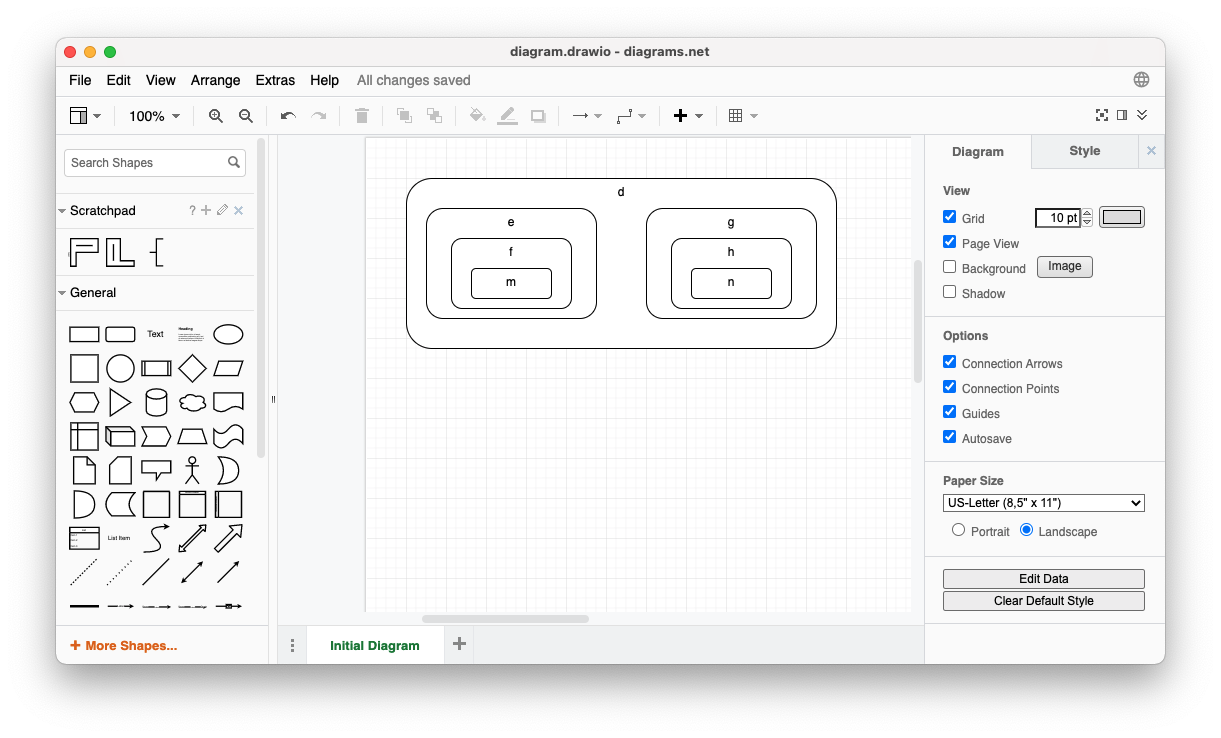

Diagram

Desired Result

In the end we want to infer the following facts:

d contains e

d contains g

e contains f

g contains h

f contains m

h contains n

Inferring Containment

I chose to do this inference in 3 steps1.

Step 1 - Raw Containment

In this step, we infer all containment, direct and indirect.

The main body of code for this inference is only a few lines:

containment(R1,R2):-

rect(R1,_),

rect(R2,_),

completelyInside(R2,R1),

format("contains1(~w,~w).~n",[R1,R2]).

The rule completelyInside uses grade-school math to calculate whether a bounding box is completely inside another bounding box.

The first 8 lines are PROLOG house-keeping, setting up variables Bl, Bt, Br, Bb, Al, At, Ar, Ab (left, top, right, bottom of B and A, resp. In an OO language, we might say B.Bl, B.Bt, etc. and forego the the first 8 lines).

The interesting part of the rule is the set of 8 comparisons, AND’ed together at the bottom of the rule.

% succeeds only if B's bounding box is fully inside A's bounding box, inclusively

completelyInside(B,A):-

l(B,Bl),

t(B,Bt),

r(B,Br),

b(B,Bb),

l(A,Al),

t(A,At),

r(A,Ar),

b(A,Ab),

Bl >= Al,

Bl =< Ar,

Br >= Al,

Br =< Ar,

Bt >= At,

Bt =< Ab,

Bb >= At,

Bb =< Ab.

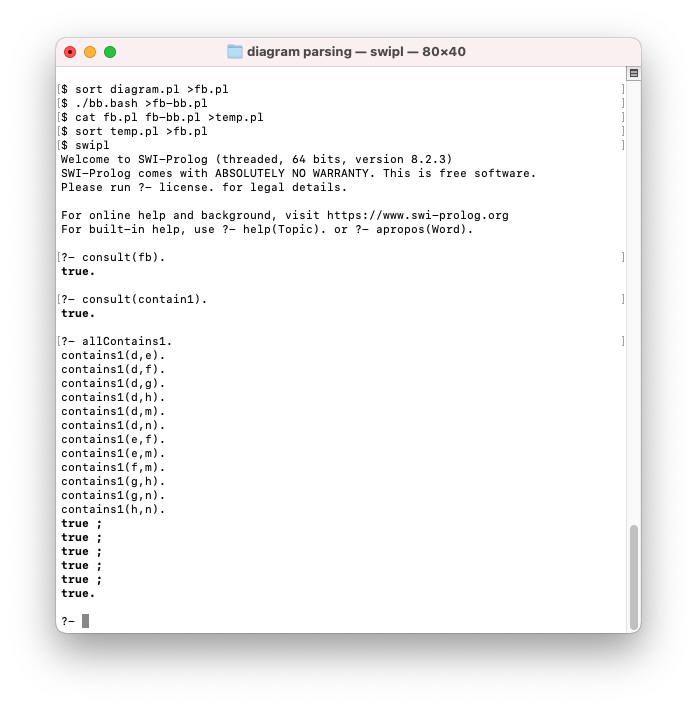

The screenshot, below, shows how to run step 1 manually and the result.

The automated version of this rule follows:

allContains1:-

bagof(R1,(rect(R1,_),rect(R2,_),R1 \= R2,containment(R1,R2)),_).

containment(R1,R2):-

rect(R1,_),

rect(R2,_),

completelyInside(R2,R1),

format("contains1(~w,~w).~n",[R1,R2]).

% succeeds only if B's bounding box is fully inside A's bounding box, inclusively

completelyInside(B,A):-

l(B,Bl),

t(B,Bt),

r(B,Br),

b(B,Bb),

l(A,Al),

t(A,At),

r(A,Ar),

b(A,Ab),

Bl >= Al,

Bl =< Ar,

Br >= Al,

Br =< Ar,

Bt >= At,

Bt =< Ab,

Bb >= At,

Bb =< Ab.

This code adds the rule allContains1. The rest of the setup is done in run.bash (see below).

The main job of allContains1 is to loop2 over all rectangles while avoiding duplicates.

Step 2

In this step, we ascertain which containments are indirect (I call them ‘deepcontains’ in this code).

PROLOG works best when it performs positive work. Negation is trickier in PROLOG. When we eye-ball the code it is “obvious” that f contains m and so on, where f is the smallest rectangle that encloses m. This relationship is harder (less obvious) to express in PROLOG. We are trying to write code that a machine can execute, hence, we break the work up into small, understandable pieces.

Most of the interesting work is done in the rule deepcontains1 and the rest of the code is setup for printing the results.

DeepContains1 consists of two OR’ed together options:

- Look for a Parent that contains, both, a Child and a GrandChild where the Child contains the GrandChild. If found, consider the Parent to deeply contain the GrandChild.

- Look for chains where Parents contain Children that contain Children that contain GrandChildren and so on. This is a recursive option. When such a chain is found, consider the Parent to deeply contain the GrandChild.

deepcontains1(Parent,GrandChild):-

contains1(Parent,GrandChild),

contains1(Child,GrandChild),

contains1(Parent,Child).

deepcontains1(Parent,GrandChild):-

contains1(Parent,GrandChild),

contains1(Child,GrandChild),

deepcontains1(Parent,Child).

deepcontains(R,Bag):-

setof(X,deepcontains1(R,X),Bag).

printContains(R):-

deepcontains(R,Bag),

printContainsSingle(R,Bag).

printContainsSingle(_,[]).

printContainsSingle(R,[H|T]):-

format("deepcontains(~w,~w).~n", [R,H]),

printContainsSingle(R,T).

printAllDeepContains:-

bagof(R,(rect(R,_),printContains(R)),_).

The results of this inference produces the new facts:

deepcontains(d,f).

deepcontains(d,h).

deepcontains(d,m).

deepcontains(d,n).

deepcontains(e,m).

deepcontains(g,n).

Step 3

At this point, we have

- All containments, direct and indirect

- All indirect (deep) containments.

We simply write a rule that filters out the indirect containments from the list of all containments and create facts (that are calledcontains) that only apply to direct containments.

Again, in PROLOG, it is easier to write positive rules (rules that find something) instead of negative rules. We would normally say that the list of direct containments is the set of containments with the deep (indirect) containments removed, but, it is easier to invent a new fact (contains) and generate it, instead of removing exiting facts3.

My code for this step is:

factContains(ParentR,ChildR):-

contains1(ParentR,ChildR),

\+ deepcontains(ParentR,ChildR).

allContainedChildren(R,Bag):-

bagof(Child,factContains(R,Child),Bag).

allContains(CBag):-

bagof([R,Bag],allContainedChildren(R,Bag),CBag).

printContainedChildren(R):-

allContainedChildren(R,Children),

printContainedChild(R,Children).

printContainedChild(_,[]).

printContainedChild(R,[H|T]):-

format("contains(~w,~w).~n",[R,H]),

printContainedChild(R,T).

printAllDirectContains:-

bagof(R,(rect(R,_),printContainedChildren(R)),_).

And, the final resulting facts are:

contains(d,e).

contains(d,g).

contains(e,f).

contains(f,m).

contains(g,h).

contains(h,n).

Which matches the desired result.

Run.bash

To automate all 3 steps, we write a simple bash script:

#!/bin/bash

sort diagram.pl >fb.pl

./bb.bash >fb-bb.pl

cat fb.pl fb-bb.pl >temp.pl

sort temp.pl >fb.pl

swipl -g 'consult(fb).' \

-g 'consult(contain1).' \

-g 'allContains1.' \

-g 'halt.' \

> fb-contains1.pl

cat fb.pl fb-contains1.pl >temp.pl

sort temp.pl >fb.pl

swipl -g 'consult(fb).' \

-g 'consult(contain2).' \

-g 'printAllDeepContains.'\

-g 'halt.' \

> fb-deepcontains.pl

cat fb.pl fb-deepcontains.pl >temp.pl

sort temp.pl >fb.pl

swipl -g 'consult(fb).' \

-g 'consult(contain3).' \

-g 'printAllDirectContains.'\

-g 'halt.' \

> fb-directcontains.pl

cat fb.pl fb-directcontains.pl >temp.pl

sort temp.pl >fb.pl

The main feature of the above code is that it does not try to do everything at once.

The work is done in 3 distinct phases, each phase producing an augmented factbase (fb.pl).

There are at least 2 reasons for this approach

- Architecture - the architecture for this solution remains clean and tidy and understandable.

- Isolation. Once a phase works, we leave it alone and don’t invite new bugs by creating hidden dependencies.

Each phase augments the factbase (cat).

We cow-tow to PROLOG’s adjacency requirements4 by sorting the factbase each time around.

Big-O

Note that big-O (O(n)) analysis is ignored here.

The only thing that matters is the final “user experience” (in this case, the programmer).

Is it “fast enough” for use?

Does it cause friction and impede free-thinking?

We are dealing with small diagrams.

Only the final speed matters.

If an operation takes 1msec to run or 10msec to run, we don’t care.

The machine (computer) certainly doesn’t care.

Keeping it small

One of the aspects of this approach is to keep all steps very small,

- for understandability,

- for isolation, and

- for UX.

A lot of computer science is devoted to handling accidental complexities which arise from “doing everything at once”.

Keeping everything small avoids such issues.

For example, global variables are only a problem in code that contains more than 7±2 lines (total). Scoping was added to make variables “local” to code and to improve locality-of-reference for when code becomes too large to understand in one gulp5.

See Also

-

It is probably possible to do this in 1 step and to make the code more efficient. Such optimizations are left up to Optimization Engineers, and do not concern Architects. The main goal of Architecture is to show one way of coding this and to make the description understandable. Corollary: if you are itching to make this code more efficient, then the Architecture is understandable. ↩

-

Bagof is, in essence, a loop. The PROLOG engine decides how to implement the loop (recursion) efficiently (maybe for each use). ↩

-

Again, PROLOG gurus might re-write this set of rules differently, maybe using PROLOG’s retract clause, but, we are writing an Architecture that can be understood by more programmers than just PROLOG gurus. ↩

-

Swipl does allow non-sorted rules, but needs extra syntactic noise. It is simple-enough to call UNIX sort after every phase. ↩

-

It was thought that libraries were a solution, but libraries tend to contain hidden dependencies, e.g. Call/Return using a hardware-assisted, hidden global variable (SP). That problem (the use of a global SP) was eliminated by adding an epicycle called threads. This new epicycle caused new accidental complexities, e.g. preemption, which led to thread safety problems … and so on.) ↩