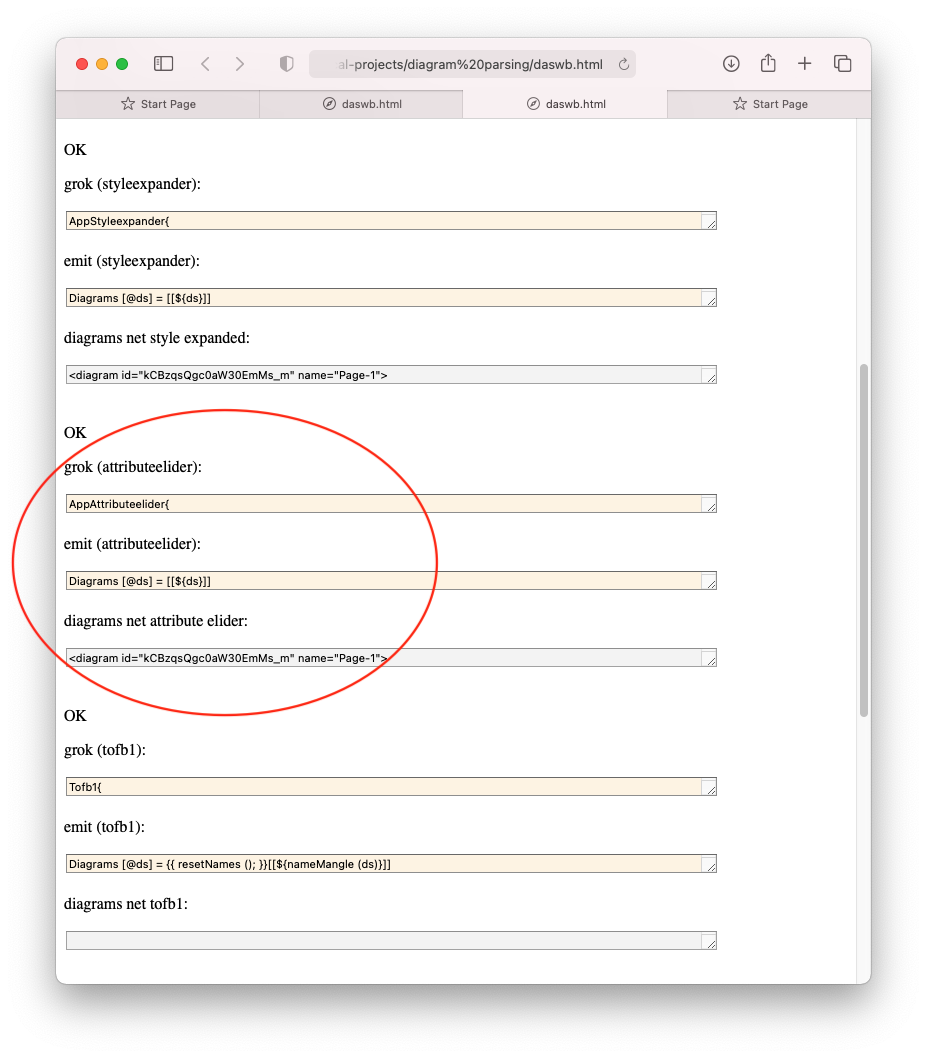

Parsing Diagrams - DaS Workbench 3 Attribute Elider Phase

Attribute Elider

The job of this phase is to filter out attributes that are not needed by subsequent passes.

This sounds like it is too specific and needs to be generalized.

In contrast, though, if the code is simple-enough, then it can be written-afresh for every solution. Programmers are used to writing fresh bits of code, say in Python, for every solution. Abstraction and generalization cannot be planned ahead-of-time - one needs at least 3 iterations before a piece of code can be generalized1.

There seems to be a very fine psychological line between writing code that feel you need to keep vs. writing code that you don’t mind discarding and re-implementing. The coding process can be untangled into 2 portions - (1) thinking-about-the-problem vs. (2) implementing (DI/Architecting vs. Implementation resp.). Once code is untangled from Architecture, it becomes possible to imagine re-implementing code while keeping what has been learned2.

Grok

The grok grammar for this pass is

AppAttributeelider{

Diagrams = Diagram+

Diagram = "<diagram" Attribute* ">" GraphModel "</diagram>"

Attribute = NameAttribute | DiagramIDAttribute | OtherAttribute

NameAttribute = "name" "=" string

DiagramIDAttribute = "id" "=" string

OtherAttribute = alnum+ "=" attributeValue

string= "\"" notDQ* "\""

notDQ = ~"\"" any

encodedChar = ~"<" any

attributeValue = number | string

number = digit+

GraphModel = "<mxGraphModel" Attribute+ ">" Root "</mxGraphModel>"

Root = "<root>" Cell+ "</root>"

Cell = CellWithContent | CellWithoutContent

CellWithoutContent = "<mxCell" CellAttribute+ "/>"

CellWithContent = "<mxCell" CellAttribute+ ">" Geometry? "</mxCell>"

Geometry = "<mxGeometry" GAttribute+ "/>"

CellAttribute = KindAttribute

| ValueAttribute

| EdgeAttribute

| VertexAttribute

| SourceAttribute

| TargetAttribute

| IDAttribute

| RedAttribute

| OtherCellAttribute

KindAttribute = "kind" "=" string

ValueAttribute = "value" "=" string

SourceAttribute = "source" "=" string

TargetAttribute = "target" "=" string

IDAttribute = "id" "=" string

EdgeAttribute = "edge" "=" quote "1" quote

VertexAttribute = "vertex" "=" quote "1" quote

RedAttribute = "fillColor" "=" quote "#f8cecc" quote

OtherCellAttribute = alnum+ "=" attributeValue

GAttribute =

OtherGAttribute

OtherGAttribute = alnum+ "=" attributeValue

quote = "\""

}

Here, the pattern matching recognizes several attributes of interest and groups all other attributes in the OtherCellAttribute match.

Note that the increase in code is offset by the decrease in “error checking”. When the workflow reaches this point, it is known that the input code can be easily pattern matched. Errors in the code format are picked off by earlier passes (as Ohm-JS syntax errors) or (as a last resort) the grammar engine of this pass.

Emit

Again, the emit code seems to be larger than in the previous pass, but the amount of programming work was trivial - the pattern matcher has done the “heavy lifting” for us.

In this code, we simply return attributes that are of interest (value, source, target, id, etc.) and return nothing ([[]] - empty strings) for the catch-all rule OtherCellAttribute.

If we were to add another attribute-of-interest, we would need to modify the grok grammar and the emit code. This is not ideal, but if this situation were to happen often, we could write another PEG parser for a new notation that outputs combined grok and emit code for the attributes-of-interest. As of now, this has not been required.

The code for attribute-of-interest returns a unity transform of the attributes and requires little work.

Diagrams [@ds] = [[${ds}]]

Diagram [k @a k2 graphmodel k3] = [[${k}${a}${k2}\n${graphmodel}\n${k3}\n]]

Attribute [a] = [[${a}]]

NameAttribute [an k s] = [[\ ${an}${k}${s}]]

DiagramIDAttribute [an k s] = [[\ ${an}${k}${s}]]

OtherAttribute [@an k s] = [[\ ${an}${k}${s}]]

string [q1 @cs q2] = [[${q1}${cs}${q2}]]

notDQ [c] = [[${c}]]

encodedChar [c] = [[${c}]]

attributeValue [x] = [[${x}]]

number [n] = [[${n}]]

GraphModel [k1 @as k2 root k3] = [[${k1}${as}${k2}${root}${k3}]]

Root [k1 @cells k2] = [[${k1}${cells}${k2}]]

Cell [c] = [[${c}]]

CellWithoutContent [k1 @as k2] = [[${k1}${as}${k2}]]

CellWithContent [k1 @as k2 @geometry k3] = [[${k1}${as}${k2}${geometry}${k3}]]

Geometry [k1 @as k2] = [[${k1}${as}${k2}]]

CellAttribute [a] = [[${a}]]

KindAttribute [kind eq s] = [[\ ${kind}${eq}${s}]]

ValueAttribute [v eq s] = [[\ ${v}${eq}${s}]]

SourceAttribute [v eq s] = [[\ ${v}${eq}${s}]]

TargetAttribute [v eq s] = [[\ ${v}${eq}${s}]]

IDAttribute [v eq s] = [[\ ${v}${eq}${s}]]

EdgeAttribute [v eq q1 s q2] = [[\ ${v}${eq}${q1}${s}${q2}]]

VertexAttribute [v eq q1 s q2] = [[\ ${v}${eq}${q1}${s}${q2}]]

RedAttribute [id k q1 s q2] = [[\ fillColor="red"]]

OtherCellAttribute [@an k s] = [[]]

GAttribute [a] = [[${a}]]

OtherGAttribute [@an k s] = [[\ ${an}${k}${s}]]

quote [c] = [[${c}]]

See Also

-

The magic number of 3 has been observed by me and is mentioned in The Mythical Man Month. “Second system syndrome” happens on the 2nd iteration. The first iteration tends to contain design errors and design oversights, the second iteration tends to be overly-general and a 3rd iteration is required to expunge the excesses contained in the second iteration. The practical answer to all of this is to keep the code as small as possible, allowing it to be discarded and written anew. The only reason to keep code is that it contains expensive work. Code is cheap, thinking is hard. ↩

-

This is one of the reasons that I use Common Lisp. When using CL, my code tends to be very small and I feel no compulsion to keep it. The opposite happened to me when I wrote code in C - the coding and the debugging costs were high, which discouraged me from discarding the code and starting afresh. This can be viewed as a UX issue (programmer UX): small differences in coding noise create a tipping-point for enormous decisions regarding keeping code or discarding it. CL allows you to build code and data quickly and to optimize it later (if necessary), whereas C (Rust, Python, etc.) encourages optimization-based thinking with high costs for coding and data creation. In such languages, optimization-concerns are inextricably wound together with architecture-concerns. ↩