Parsing Diagrams - DaS Workbench 5 Factbase Emitter

Factbase Emitter

This phase emits relations (triples) from the original .drawio diagram.

This phase does not collect names, since that was already done in the previous phase.

This phase does no design-rule checking (aka error checking), since that was all handled in previous passes. We can pay attention only to the issue(s) of code creation.

This phase uses the name table created by the previous phase. See the function refID() in support.js.

One of the simplicities of emitting a factbase of triples is that no order is required - we can just emit code as we walk the input.

This is the ideal for machine-readable code generation - no output order required.

If we were, say, to emit code in C1, then we would have to worry about ordering and declaration before use in the resulting code. We would probably need to store code in buffers and a graph instead of creating code on-the-spot. The final graph would be walked, in some traversal order, to produce the final output string.

[The macro processor M4 provides the ability to emit code into various buffers.]

We have avoided the need for buffering and graphing, by splitting the final emitter into two phases (name collector, emitter) and emitting code into an unordered factbase of triples.

We happen to create triples in PROLOG syntax, although it should be easy to create triples in some other syntax (skin).

Grok

Grok

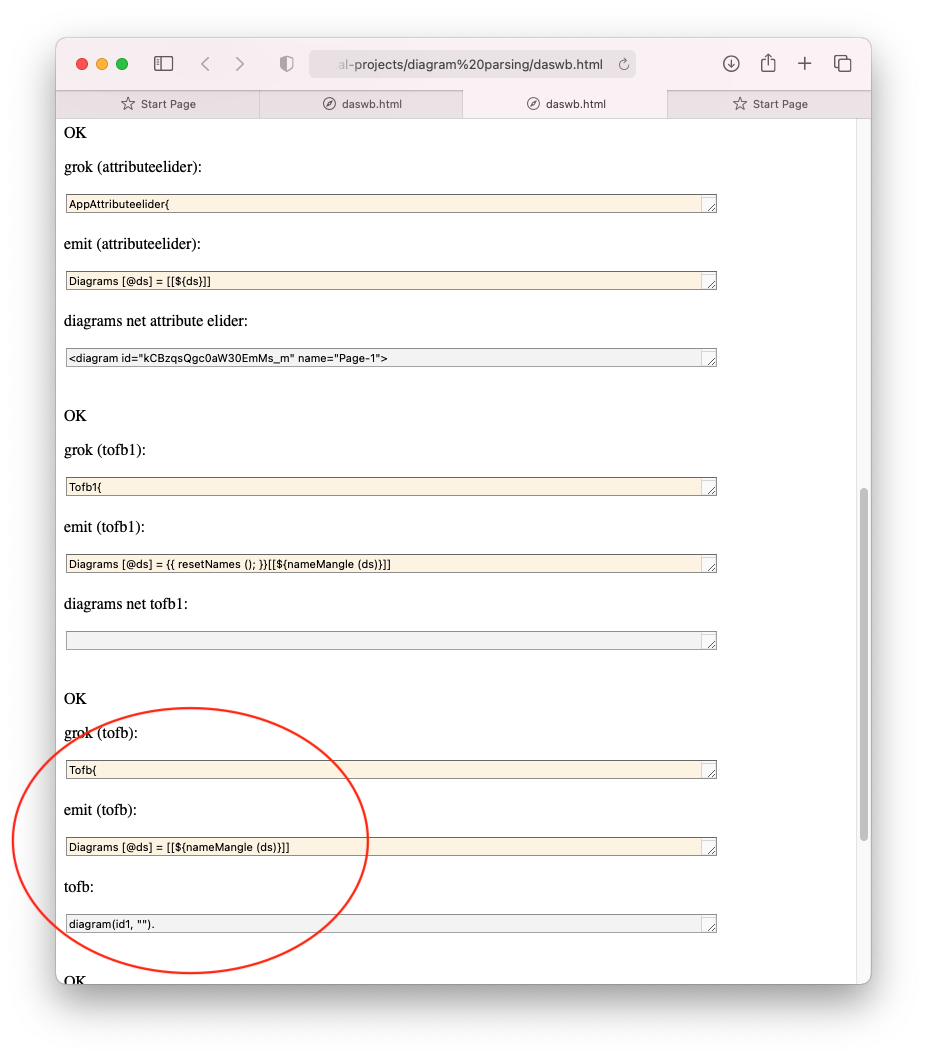

The grok grammar is the same as for the preceding pass (name collector). The input to this phase is exactly the same as the input to the preceding phase.

Emit

The work is done in the emit code:

Diagrams [@ds] = [[${nameMangle (ds)}]]

Diagram [k @a k2 graphmodel k3] = [[${a}${graphmodel}]]

Attribute [a] = [[${a}]]

NameAttribute [an k s] = [[name(${getDiagramID()}, ${s}).\n]]

DiagramIDAttribute [an k s] = [[${pushDiagramID (s)}diagram(${getDiagramID()}, "").\n]]

OtherAttribute [@an k s] = [[\ ${an}${k}${s}]]

string [q1 @cs q2] = [[${q1}${cs}${q2}]]

unqstring [q1 @cs q2] = [[${cs}]]

notDQ [c] = [[${c}]]

attributeValue [x] = [[${x}]]

number [n] = [[${n}]]

GraphModel [k1 @as k2 root k3] = [[${root}]]

Root [k1 @cells k2] = [[${cells}]]

Cell [c] = [[cell(${getCellID()},"").\ncontains(${getDiagramID()}, ${getCellID()}).\n${c}]]

CellWithoutContent [k1 @as k2] = [[${as}]]

CellWithContent [k1 @as k2 @geometry k3] = [[${as}${geometry}]]

Geometry [k1 @as k2] = [[${as}]]

CellAttribute [a] = [[${a}]]

EllipseAttribute [kind eq q1 s q2] = [[ellipse(${getCellID()}, "").\n]]

TextAttribute [kind eq q1 s q2] = [[text(${getCellID()}, "").\n]]

KindAttribute [kind eq s] = [[kind(${getCellID()}, ${s}).\n]]

ValueAttribute [v eq s] = [[value(${getCellID ()}, ${s}).\n]]

SourceAttribute [v eq s] = [[source(${getCellID ()}, ${refCellID(stripQuotes (s))}).\n]]

TargetAttribute [v eq s] = [[target(${getCellID ()}, ${refCellID(stripQuotes (s))}).\n]]

IDAttribute [id eq s] = [[${pushCellID (s)}]]

EdgeAttribute [v eq q1 s q2] = [[edge(${getCellID()}, "").\n]]

VertexAttribute [v eq q1 s q2] = [[vertex(${getCellID()}, "").\n]]

RedAttribute [id k q1 s q2] = [[fillColor(${getCellID()}, "red").\n]]

OtherCellAttribute [@an k s] = [[]]

GAttribute [a] = [[${a}]]

ASGAttribute [kas k s] = [[]]

RelativeGAttribute [r k s] = [[]]

xGAttribute [an k s] = [[${an}(${getCellID()}, ${s}).\n]]

yGAttribute [an k s] = [[${an}(${getCellID()}, ${s}).\n]]

widthGAttribute [an k s] = [[${an}(${getCellID()}, ${s}).\n]]

heightGAttribute [an k s] = [[${an}(${getCellID()}, ${s}).\n]]

OtherGAttribute [@an k s] = [[${an}(${getCellID()}, ${s}).\n]]

quote [c] = [[${c}]]

The code is straight-forward.

NameMangle() is used to convert - characters into __ characters to appease PROLOG syntax requirements2.

Furthermore, the grammar parses strings and includes the double-quotes in the parsed text. StripQuotes() is used to remove the double quotes during table lookup. It would have been possible to leave the quotes in, but removing the quotes helped debug-ability (human readability vs. machine readability).

A representative example line of code from the emit section is:

VertexAttribute [v eq q1 s q2] = [[vertex(${getCellID()}, "").\n]]

Here, after matching a VertexAttribute rule, we are given 5 sub-matches. We simply emit vertex(..., "") while pulling the most-recent cell ID from the table (using getCellID()).

The only subtlety in the code is the use of the push-down scope stack (scopeAdd()). We push the cell ID onto the scope stack when we encounter an mxCell element.

The ID is pushed in the preamble code, surrounded by double-brace-brackets ``. This code is evaluated before the rest of the CST is walked (“downwards”).

All subsequent attributes are applied to this ID.

The scope stack is automatically popped under-the-hood by the glue engine.

We do something similar with the diagram ID, in the diagram rule.

In general the scopeStack is used to track scoping in a stack-like manner and to tie this information to the grammar. Attribute grammars were invented to do this, e.g. to set attributes on the “way down” and to use those attributes on the “way back up”. Function calls also do this kind of thing but cause it to happen in every call instead of being used sparingly. Note that this is a form of “dynamic scoping” instead of “static scoping”. Pre-CL Lisps used dynamic binding for all scoped variables, then, programmers switched to using static scoping for all variables. A mix of the two techniques gives more flexibility in the end. A grammar defines a static AST at compile time, but at runtime, the grammar results in a dynamic traversal of a CST. [Note that the rules of Common Lisp make it possible to create dynamically scoped variables in addition to the default statically scoped variables.]

Result

The result of the emitter phase is listed below:

diagram(id1, "").

name(id1, "Page__1").

cell(id2,"").

contains(id1, id2).

cell(id3,"").

contains(id1, id3).

cell(id4,"").

contains(id1, id4).

value(id4, "m").

vertex(id4, "").

x(id4, 120).

y(id4, 80).

width(id4, 440).

height(id4, 210).

cell(id5,"").

contains(id1, id5).

value(id5, "n").

vertex(id5, "").

x(id5, 180).

y(id5, 120).

width(id5, 320).

height(id5, 140).

cell(id6,"").

contains(id1, id6).

value(id6, "b").

ellipse(id6, "").

vertex(id6, "").

x(id6, 540).

y(id6, 175).

width(id6, 30).

height(id6, 30).

cell(id7,"").

contains(id1, id7).

source(id7, id8).

target(id7, id9).

edge(id7, "").

cell(id8,"").

contains(id1, id8).

value(id8, "a").

ellipse(id8, "").

vertex(id8, "").

x(id8, 110).

y(id8, 175).

width(id8, 30).

height(id8, 30).

cell(id9,"").

contains(id1, id9).

value(id9, "c").

ellipse(id9, "").

vertex(id9, "").

x(id9, 174).

y(id9, 175).

width(id9, 30).

height(id9, 30).

cell(id10,"").

contains(id1, id10).

source(id10, id11).

target(id10, id6).

edge(id10, "").

cell(id11,"").

contains(id1, id11).

value(id11, "d").

ellipse(id11, "").

vertex(id11, "").

x(id11, 474).

y(id11, 175).

width(id11, 30).

height(id11, 30).

This result lists triples in an unsorted factbase.

PROLOG grammar requires that facts be grouped together, though. The final phase sorts the list (in alphabetical order) making it acceptable to PROLOG.

See Also

-

It is even “harder” to emit Python code, since, we have to wrorry about creating indentation in the output string. ↩

-

Note that we convert a single dash into two underscores. This ensures that the converted dashes cannot conflict with existing legal uses of the underscore character. The human-readability of the emitted code is only important during bootstrapping and debugging. After that, we only need to generate machine-readable code (we could use Drawio’s “unreadable” ids - the machine doesn’t care about the appearance of ids). ↩