Addressing

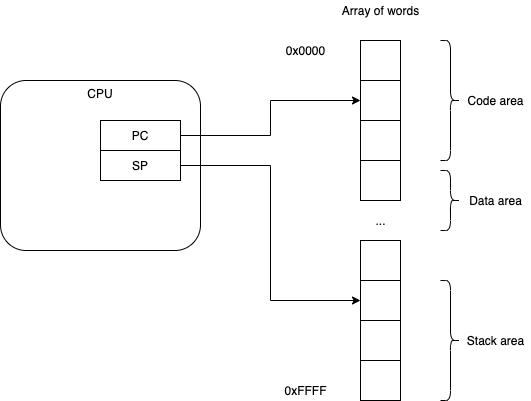

Absolute Addressing

Simplest case - the CPU directly addresses memory.

Memory is implemented, in hardware, as an array of bytes/words.

Every program has 3 spaces:

- code

- initialized data

- stack.

Local variables (scoped data) and temporaries are usually placed on the stack.

Global variables are usually placed in the initialized data area.

Code can be in read/write RAM, or, code can be placed in read-only ROM, or, code space can be protected from writes by hardware (not shown).

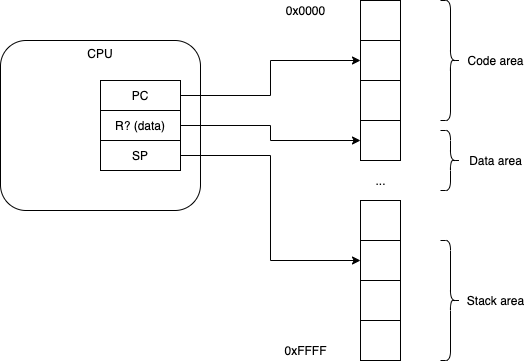

Relative Addressing

Compilers determine what kind of code is created for a program.

For relative addressing, compilers emit references to data as offsets from some distinguished register (usually chosen by the compiler-writer).

Locals are referenced as offsets from the SP register (Stack Pointer).

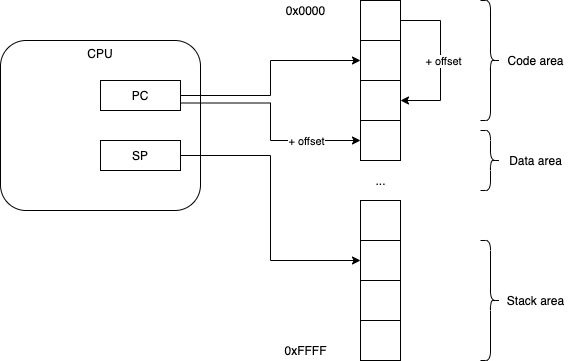

PIC - Position Independent Code

To allow code to be repositioned in memory (e.g. when loaded by the operating system), compilers are made to emit all offsets (data and control flow) relative to some register, e.g. the PC (program counter).

Control-flow instructions, like branches, do not refer to absolute locations, but are made relative to some register. For example, BR label (branch to label) is compiled as BR offset+PC (where offset is the integer offset of the label relative to the current code position).

Note that relative addressing makes writing compilers a bit harder, since the compiler programs need to calculate offsets instead of emitting absolute labels.

Some CPU instruction sets make it hard/impossible to use relative addresses.

Some CPUs take longer to calculate and use a relative address than to use an absolute address.

Some CPU architectures provide compiler-writers with special registers that are set for every function call to point to a fixed data location and all label offsets are calculated relative to those registers. Unlike the PC, the special offset-registers don’t change value during function execution.

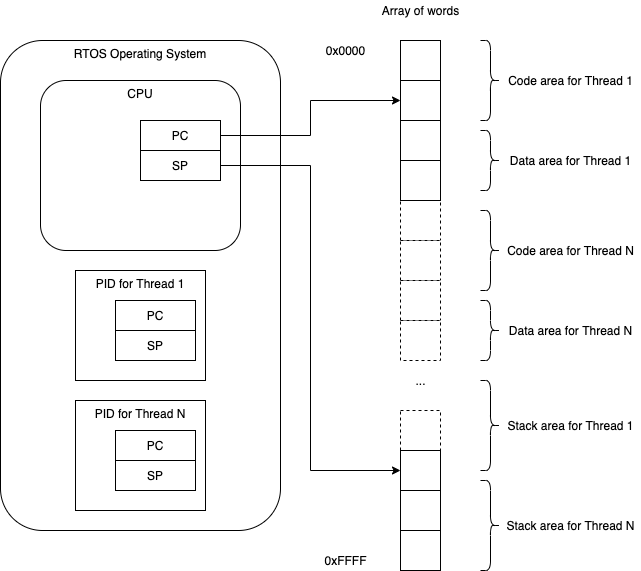

RTOS - Embedded Operating System

In a simple embedded operating system that supports threads, memory is divided up between threads.

Each thread is given its own code/data/stack area.

Obviously, a buggy program might overwrite data/code/stack of some other thread, crashing the whole system (or worse, continue running and cause mysterious bugs and crashes later).

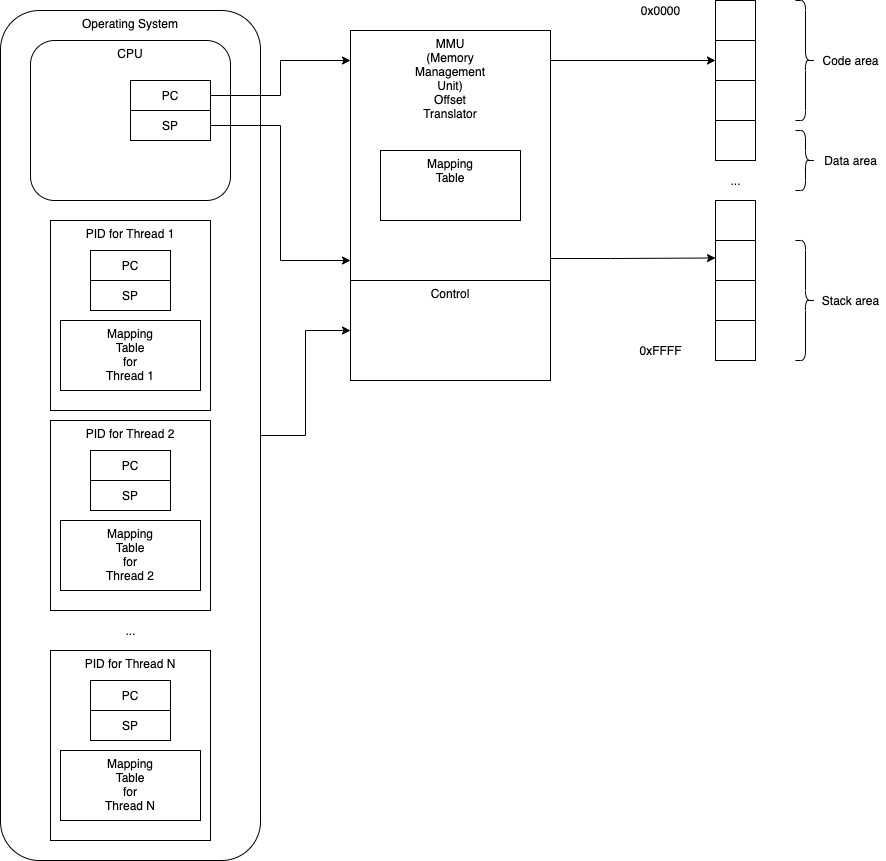

MMU - Memory Management Unit

Some hardware designs provide hardware memory protection and segmentation using MMUs (Memory Management Units ; extra ICs and/or built-into the CPU).

MMUs hold a mapping table for the current thread and map addresses when memory is accessed.

This makes it possible to use absolute addressing (again), since the hardware will map absolute addresses into actual addresses.

The Operating System must keep a unique mapping table for each process and must load the mapping table into the MMU hardware before resuming a process.

Larger Operating Systems will “optimize” memory by writing out a thread’s memory to disk when it is suspended and by reading back in a thread’s memory when it is resumed. This is called swapping and paging.

Q: What is the time cost of using a mapped address instead of an absolute address?

Q: What is the cost ($) of using an MMU chip or a CPU-with-MMU in a design?

Virtual Memory

Virtual memory is a variant of the way in which MMUs are used.

Not all of a thread’s memory is read back in from disk at once.

When the thread tries to access a block of its own memory that is not already in-core, the MMU signals an interrupt. The operating system fields the interrupt and pages-in the appropriate block of memory, then resumes the thread and allows it to continue running.

This is an optimization based on the hope that a thread will block before it accesses all of its memory. Since it is orders-of-magnitude more costly (in time, say), to access memory on a disk, the operating system hopes to save time by not paging in all memory until it is actually needed.

Blocking

A thread blocks by yielding to the Dispatcher (the operating system).

-

Blocking can be voluntary, i.e. when a thread asks for some I/O that takes a long time, or,

-

Blocking can be involuntary, i.e. when the operating system decides that a thread has run “long enough”. Usually, the operating system sets a hardware timer and waits for a timeout or a voluntary block.

Complexity

As can be seen, multi-threading is quite simple.

Each extra layer of hardware-assist adds more complexity to the code. Most often, the code is squirreled away into a library that we call the operating system.

Q: What is the trade-off between complexity and hardware-assist?

Q: Is it better to have 1,000 8-bit, simple CPUs on a chip running simple operating systems, or is it better to have an MMU and more complication in the operating system?