ė - Concurrent Lambdas Working Paper (March 20, 2022)

Looks like a function from the outside, but runs a dispatcher internally, allowing sensible diagrams to be drawn.

lookup.asd (lisp project file)

working diagram rough cut see lookup tab(s)

Update 2022-04-10

I am debugging this… [If you see my problem, please email me :-]

I draw my “code” using draw.io, then hand-transpile it to text[^txt] then use Ohm-JS to transpile the pseudo-code to JavaScript…

Code

[Beware. This program is currently being debugged and the above may contain inconsistencies.]

Revelation

- concentric boxes

- means synchronous execution

- means inheritance (downwards and upwards, e.g. return value bubbles back up to the output of the outer-most box without needing an explicit wire)

- boxes with ports and wires

- means concurrent execution

- boxes are “black boxes” (you don’t/can’t care what is inside)

- scheduler/dispatcher for concurrency is built-into the emitted code as closures (anonymous lambdas)

- what we call “parameters”

- e.g.

f(x,y,z) ... - is not plural but singular - it is a single block of data which is de-structured into several sub-types

- the singular block of data is synchronous - all data in the block arrives “at the same time”

- the same with return values (one block of data, synchronous),

- asynch parameters can arrive “at any time” (the code must be written in the concurrent paradigm), e.g.

f(p,q,r)(u,v,w)(x,y,z)->(a,b,c)(d,e,f) - asynch sends (aka return values) can be produced “at any time”

- asynch sends do not cause blocking of the caller

- asynch sends can go to any receiver (not just back to the caller)

- asynch thinking allows for multiple input ports, multiple output ports, no input ports, no output ports (what is a

daemon?) ;functions, though are limited to exactly one input port and exactly one output port and cause the caller to block ; (to re-iterate, my use of the termportimplies a superset of what we commonly callparameters(one port === one block of parameters, regardless of how many parameters are in the block))

- e.g.

Loop

loop:

call function to test for termination

call function to do work

continue

end loop

Note that the do work () function might call a done () function that affects the termination test - the next time around.

Refinement, more detail:

begin ()

loop:

call function to test for termination

call function to do work

continue

end loop

finish ()

Each Loop is made of 3 pieces

- beginning

- middle

- end.

More refinement, even more detail:

anonymous wrapper {

define mutable boolean done_flag = false;

define conclude () { done_flag = true; }

begin ()

loop:

call function to test for termination (done_flag === true?)

call function to do work

continue

end loop

finish ()

}

Mutability - bad in general, but, OK when restricted.

Flag === mutable variable.

The above restricts the use of the flag. The flag cannot be mutated explicitly by the programmer. The flag can only be implicitly mutated by the programming language (e.g. by calling conclude () or whatever syntactic sugar is provided by the language).

Note that the loop contains two (2) function calls. These can be written in a functional manner.

The loop/flag is lifted out of the functional paradigm (leaving the functional paradigm simple, and, un-bloated) (See Tunney’s Sector Lisp for beautifully simple use of the functional paradigm. Tunney removed bloat and reduced the whole language to <512 bytes[sic]).

Bloatware, like Linux, MacOS, Windows, etc. tries to enable mutation in a paradigm (functional) that resists mutation. The result is bloatware. Note that the above Loop is understandable and cannot need 1Mb of bloatware to support it.

Note that assembler is full of flags and mutation and globals and otherwise disgusting concepts. We wrap HLLs around assembler (e.g. Haskell, C++, Python, JS, etc.) to hide the disgusting concepts and to restrict their use. But, then, we insert the disgusting concept of synchrony in at the lowest levels.

Most of our programming languages allow bloated concepts like synchronization-everywhere, and, mutation, and, … I argue that we should lift these concepts out of the beautifully-simple paradigms, stop trying to force one language to do everything and use Ohm (a derivative of PEG) to wrap many syntaxes around the paradigms. Then, we can choose syntaxes to suit our problems instead of having the language-designers tell us how to solve our problems.

Creating syntax (a language) used to be hard.

With Ohm, syntax is no longer hard.

Languages are like bowls of candies, grab a handful.

The underlying paradigms are still “hard to understand”, but we can drape them in less-hard-to-understand syntaxes.

We can create a cookbook of various syntaxes for programmers who don’t want to create their own syntaxes.

Layers: some programmers know best how to create GUIs, some know security, etc, etc. Give them each a bowl full of syntaxes. Some programmers are good at creating syntaxes for other programmers - give them syntaxes for creating syntaxes.

Unanswered question: how do we compose applications using many pieces and how do we compose applications that use pieces that are composed using other pieces (it’s turtles all the way down)? Synchronous code and libraries ain’t the answer… Depedencies are bad1.

Programming languages are IDEs.

Programming language IDEs were invented in the mid-1900s based on the pathetic hardware of the day. The hardware has improved, but we continue to use mid-1900s style languages.

Loop vs. Concurrency

Loop is, actually, more “complicated” than concurrency.

loop:

call function to test for termination

send message to leaf to perform 1 step

call leaf function

continue

end loop

concurency:

call function to test for termination

call container function to do work

continue

end loop

The “difference” between traditional looping and concurrency is:

- loop calls a Leaf function

- the Leaf function performs 1 step of the loop, then returns

- the Loop sends a

continuemessage to its inner function, when looping, - or, the loop exits when the termination condition is

true, without sending a ` continuemessage to its inner function (in fact, even if it did send acontinue` message in this case, the message would never be processed, since the Loop would exit and not call its inner function)

- the concurrency loop calls a Container function

- The Container performs one step, recursively

- the Container is a recursive function that may contain nested functions

- nested functions can be Leafs, Loops or other Container functions

- somewhere in the bowels of the nested functions, the continuation flag is set/reset

- the nested functions send messages to other functions (but indirectly)

- the routing of messages is performed by the nested-functions’ direct parents (always Containers)

- the concurrency loop does not need to send itself a

continuemessage, the nested functions send messages as required and keep the loop going, or, one of the nested functions tells the loop to stop - stopping concurrency does not happen immediately, but only at the top level

- the loop wrapper can stop looping if there are no messages (recursively) to be processed

- in general, a message is not processed in one fell swoop, but is processed in steps where the steps are meted out by the loop and the recursive tree of Containers

- The Container performs one step, recursively. Each Container tells its Children to perform one step. If the Child is a Container, then it tells its Children to perform one step, and so on. If the Child is a Leaf, the Leaf performs its step and simply returns.

A “game” world would be a Concurrency Loop that steps until it has changed the world. It returns the modified World. The game Loop would store this modified World for use in the next go-around.

Makng all code concurrent makes it possible to optimize the code by splitting pieces onto other machines (distributed).

Note that synchronous languages inhibit such splitting. E.g. Python, JS, Haskell, libraries, etc.

Splitting is possible using synchronous languages, but is more complicated (we invent bloatware like Linux, Window, MacOS, etc. to help with the splitting).

Splitting is “natural” on the internet. Synchrony inhibits splitting and, therefore, inhibits full realization of internetting. We end up with contortions like callbacks and CPS.

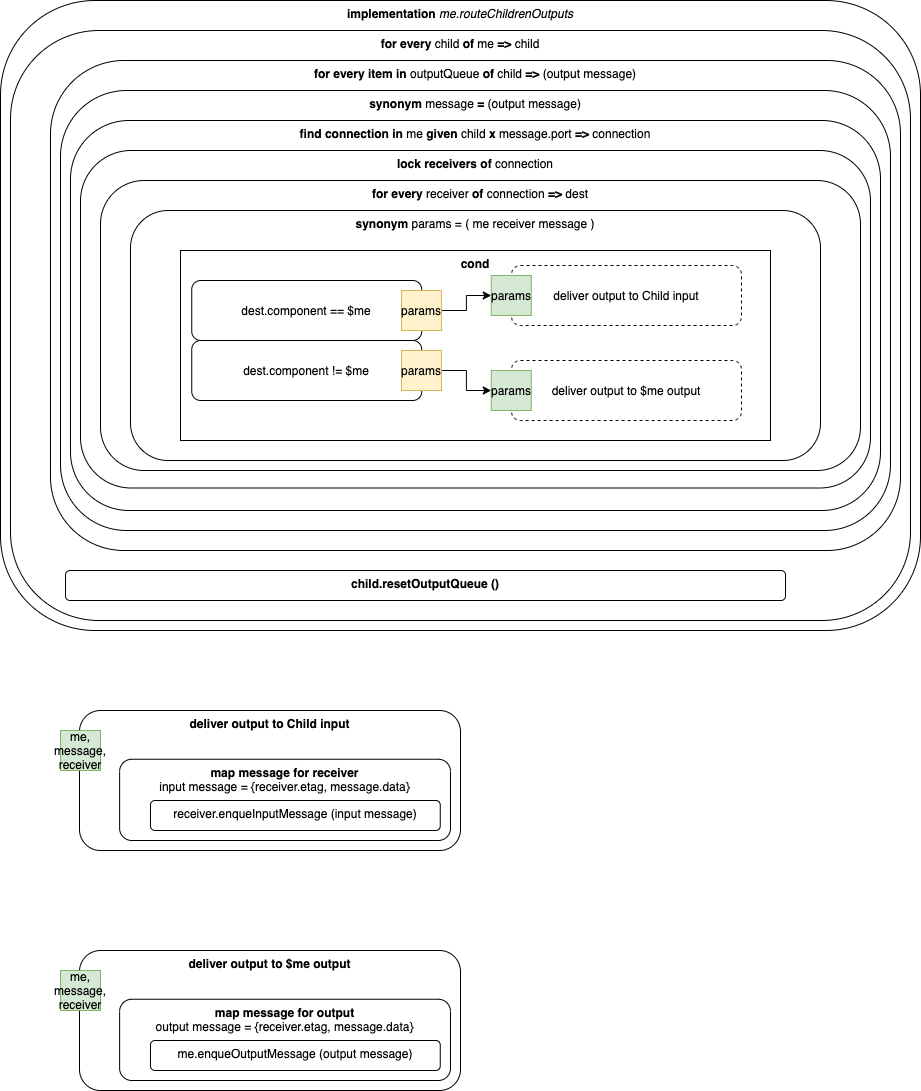

Pseudo-Code

[This is actual code from an actual project. Don’t worry about what is being implemented, look only at how it is being implemented (the syntax, the transpiler(s)).]

implementation route

{ for every item in children of me => child

{ for every item in outputQueue of child.runnable => output_message

{ synonym message = output_message

{ find connection in me given child X message.port => connection

{ lock receivers of connection

{ for every receiver in connection => dest

{ synonym params = {me, message, receiver}

{ cond

{ dest.component != me

{ @deliver_output_to_child_input <= params }

}

{ dest.component == me

{ @deliver_output_to_me_output <= params }

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

{@child.runnable.resetOutputQueue}

}

}

sync deliver_output_to_child_input <= me, receiver, message

// map message for receiver

{ var input_message <= {receiver.etag, message.data}

{ @receiver.enqueueInputMessage <= input_message }

}

sync deliver_output_to_me_output <= me, receiver, message

// map message for output

{ var output_message <= {receiver.etag, message.data}

{ @me.enqueueInputMessage <= output_message }

}

JavaScript

exports.route = function () {

var _me = this;

var _ret = null;

_me.children.forEach (child => {

child.runnable.outputQueue.forEach (output_message => {

var message = output_message;

var connection = this.find_connection_in__me (child, message.port);

// locking only matters on bare metal (async)

connection.receiver.forEach (dest => {

var params = [_me, message, receiver];

if ((dest.component !== _me)) {

deliver_output_to_child_input (params);

} else if ((dest.component === _me)) {

deliver_output_to_me_output (params);

}

});

});

child.runnable.resetOutputQueue ();

});

return _ret;

}

this.deliver_output_to_child_input = function (_me, receiver, message) {

var input_message = [receiver.etag, message.data];

receiver.enqueueInputMessage (input_message);

}

this.deliver_output_to_me_output = function (_me, receiver, message) {

var output_message = [receiver.etag, message.data];

_me.enqueueInputMessage (output_message);

}

Future

Once you have worked out the mechanisms for internal concurrency, it becomes “easy” to imagine other kinds of things, like internal state-tracking and Loop-ing…

- state machine lambdas (calls functions written as pure FP lambdas, receives a result, stores it, follow Harel-like StateChart hierarchy to enter/exit states)

- Loop lambda (calls function(s) written as pure FP lambdas, repeat)

- one function as predicate - exit loop? continue looping?

- one function as body of loop prior to predicate test

- another function as body of loop after predicate test

loop{callbody1(),exit whentest(),callbody2() }

One should be able to “compose” pure functions with concurrent lambdas with state-machine-lambdas with loop-lambdas.

ė

As a working title for this concept, I’m going to use ė.

It is the Lithuanian letter “e” with a dot above it.

It is pronounced like Canadian “eh” or the English-language letter “A” (hard, not soft).

I almost chose another Greek letter, then realized that I could use any unicode character, then, almost chose a smily emoji, but, finally settled on ė.

[The choice is almost arbitrary, but, ė ties my two inherited cultures together.]

Syntax Is Cheap

We need a toolbox that contains the Atoms of software. Something like:

- pure functions (e.g. Sector Lisp, Lambda Calculus)

- state (history)

- looping.

Then, we can glue the Atoms together using any syntax we choose.

Syntax - language design - is equivalent to building up molecules using atoms.

PEG allows us to break out of the syntax prison. (Including the use of multiple languages (e.g. using balanced paren-matching))

Ohm-JS is even better than PEG.

FP taught us that variable names are inconsequential (in fact, this can also be understood by building compilers).

In my view, syntax is equally inconsequential.

Pattern Matching

FP teaches that pattern-matching is King.

Parsing is pattern-matching.

PEG is better-parsing.

Ohm-JS is better-PEG.

Looping

We don’t need TCO - tail-call-optimization.

We only need Looping.

TCO is make-work activity - an attempt to kludge looping into the functional paradigm.

We need a way to compose looping with pure functions.

We do not need to add epicycles to the functional paradigm, nor to devise clever tricks that allow us to use the functional paradigm everywhere.

Sector Lisp is a wonderful example of a bloat-less functional paradigm.

Rhetorical Q: How do we compose Sector Lisp with Loop and State?

In my view,

- Loop is a thing on its own.

- State is a thing on its own.

- Pure Functional is a thing on its own.

In my view, don’t jam them all together, snap them together in new ways for every specific problem.

Deprecating Loop and Recursion

Note that Looping doesn’t even make sense in a distributed computing environment.

A language for distributed computing does not have Loop (or Recursion) as a fundamental concept.

A Component can always Send messages to itself if it wants to repeat a computation.

Looping and Recursion imply the use of a Stack. This doesn’t make sense in a distributed environment.

A single CPU can have a single Shared Stack, but the idea of a Stack doesn’t translate well into something that is sent on a thin wire.

The concepts of Loop and Recursion and Stack are so in-grained in our thinking that we feel it necessary to (cleverly) invent epicycles, like preemption, to accomodate long-running Loops.

These epicycles have caused us unanticipated grief in the past, e.g. priority inversion in the Mars Rover disaster (see my blog).

On Diagrams

Diagrams - to normal humans - imply concurrency.

Boxes / ellipses / blobs on a diagram look like isolated entities. And, that’s how humans interpret diagrams.

Software is - currently - very synchronous. As such, software programs defy diagramming.

It is possible to draw diagrams of computer networks, because each computer on the network is isolated from the others (they synchronize only when they have to, otherwise, they run at their own speed (without implicit synchronization))).

It is possible to draw sensible diagrams of large chunks of software.

It is not possible to draw sensible diagrams of software at a fine grain, due to implicit synchronicity (for example, see my blog “CALL/RETURN Spaghetti”).

There are 2 options:

- Accept the fact that all programs, below a certain level, cannot be diagrammed. You are stuck with lumps like Linux to shepherd isolated envelopes containing fancy calculators.

- Find a way to optimize concurrency down to a lower level. I propose Concurrent Lambdas (working name). I think that every function should be concurrent (in fact, I’d be happier if every statement (line of code2) were concurrent, but, small steps first (

parand thread libraries ain’t it))). In my view, Components send messages to one another - they cannot call each other directly. For added flexibility, messages cannot be sent directly to peers, but must be sent upwards to the parent (Container) for routing. Structured message-passing is hierarchical.

Drop-Dead Simplicity

The mechanism for interal concurrency is ridiculously simple. Like the concurrency used in early computers

- do something

exit whensome condition is met- poll inputs

- loop back to (1)

Preemption is a tell - a bad smell - that something is wrong / too-complicated.

In fact, preemption allows us to disobey the principle of locality-of-reference. Blocking is done in two disparate places:

- The Operating System

- CALL / RETURN.

The O/S does preemption by pulling the rug out from under an app.

The only reason that the O/S needs to do this is to allow for long-running Loops.

Preemption should be relegated to development systems.

Well-behaved apps (i.e. products) should not interfere with one another and, hence, don’t need preemption.

The only reason that product apps might mis-behave is that they are too complicated to understand (and tame).

First-Class Functions and Closures

Operating systems implement closures in assembler and C.

The reason for this is bigotry.

Assembler and C programmers thought that Lisp and other dynamic languages weren’t “as good” as C and assembler, so, they built part-of-lisp in raw assembler and C, the hard way, in an act of self-flagellation.

I suggest that we put concurrency directly into first-class functions and closures and get rid of Operating Systems.

Concurrency Is Not Parallelism

Concurrency is a life-style.

Parallelism is a greasy hamburger.

Rob Pike Concurrency Is Not Parallelism

It is possible to write programs that are concurrent but not parallel.

It is not possible to write programs that are parallel without, first, being concurrent.

Maybe concurrency is orthogonal to functions? Like control-flow is orthogonal to data-flow. (When you try to schmoo them together, you get a mess of complication).

Concurrency is a paradigm.

Parallelism, though, is simply a problem-to-be-solved. An optimization.

See Also

Table of Contents

Blog

Videos

References

Books

-

In fact, lines of code are so mid-1900s. I advocate switching to diagrams. Diagrams can contain text (i.e. text is a subset of diagramming). A unit of programming is The Component (concurrent), not the line-of-code (or function). N.B. It is silly to draw diagrams of things that are perfectly fine as text, e.g. “a = b + c”, but, there are other concepts that can only be meaningful as diagrams (e.g. networks of Components (where Components are not restricted to being 1-in-1-out things (M-in-N-out, where N >= 0 and M >= 0 [sic - 0]))). A network can be represented as text, but, I don’t find that meaningful (except as assembly code and core dumps). ↩