JS Objects

Synopsis

This is my understanding of how JavaScript objects are stored, before optimization.

[This is WIP - I’m trying to understand JS by taking it apart and atom-izing it.]

Everything Is An Object

Everything is an object, including functions.

Except Atomic Things

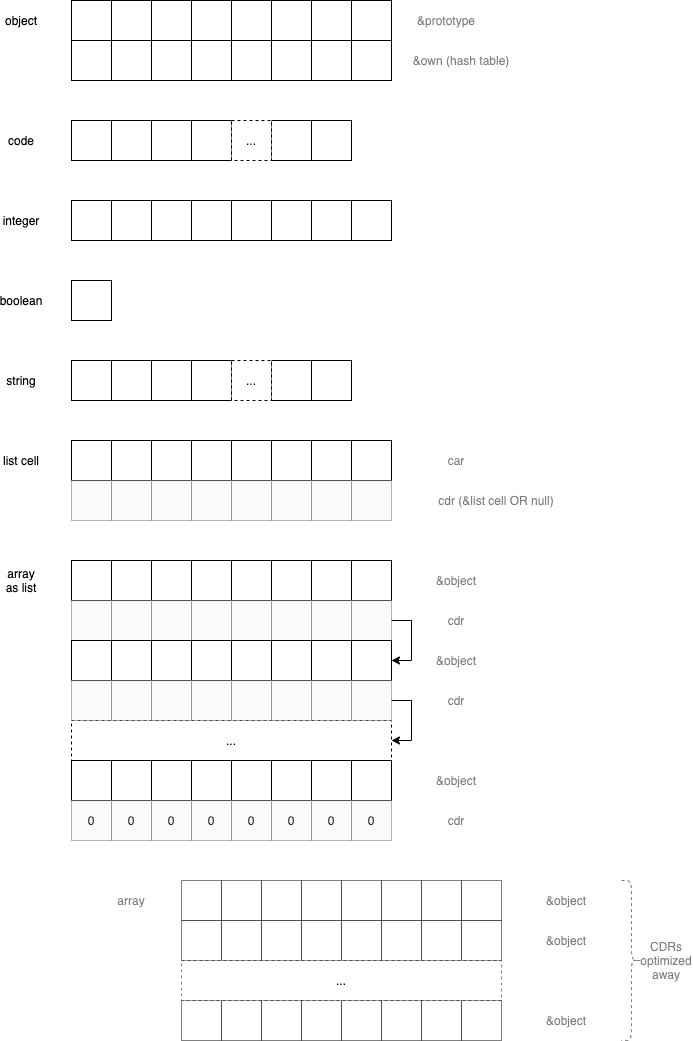

- code is atomic - it is probably a blob of bytes, maybe a string of source code(?)

- integers are probably atomic

- booleans - true/false - are probably atomic

- strings are atomic - probably a blob of bytes

- the two-slot tuple (struct) that represents objects is probably atomic

-

list cells are atomic

- (arrays are made of atomic list cells)

- (continguous arrays of objects can be optimized (to remove CDRs))

Drawing - Atomic Structures

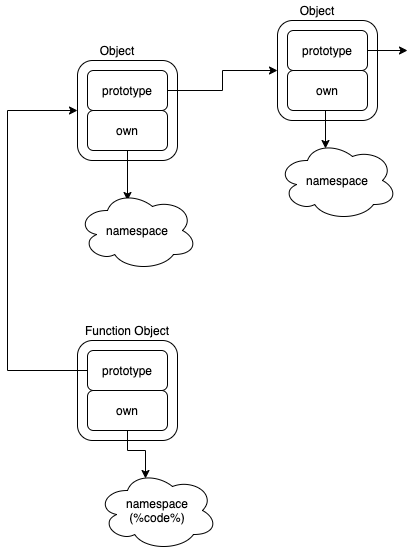

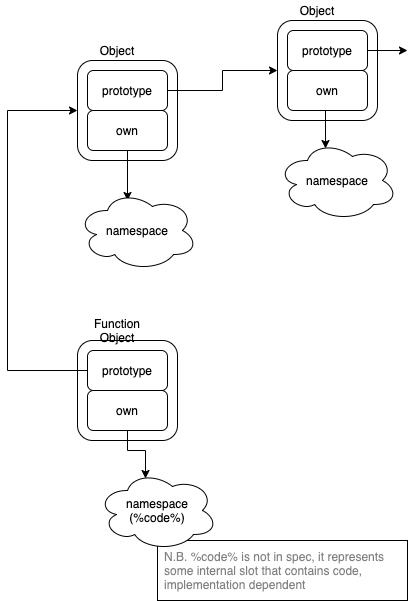

All Objects Have Two Slots

Prototype Is A Pointer to Another Object

Own Is A Namespace

A namespace is a lookup table.

Each row in the table maps a string name to an object.

Namespaces could be implemented as hash tables.

Names “point” to objects, either function objects or other kinds of objects. (Both kinds of objects are the same).

Magic Slot for Code

Function objects contain a “magic name” that points to a code blob.

The name is entirely implementation-dependent.

I invented the name %code% as a stand-in for the name of this magic slot. I treat % like just a character that can’t be confused with any other character allowed in JavaScript programs.

Function Call Syntax

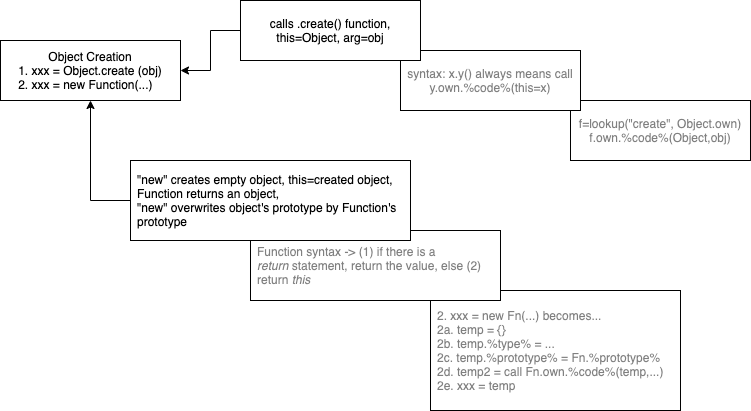

There are two fundamental ways to create an object

- Object.create()

- new

There are other ways to create objects, like class, but these are built upon the fundamental operations. Class is like a molecule built out of atoms.

Object.Create

Object.create() is a method call on the top level Object object.

New

var x = new YYY (...)

The new statement calls a “regular” function in a special way…

(New calls the function, but inserts pre- and post- code around the call.)

All methods (functions) are called with a this parameter.

f.x (y)

is converted to

call f.%own%.%code% with parameters (f, y)

which becomes

f.%own%.%code%.call (f, y)

(where %own% and %code% are names that I invented to represent implementation-dependent ways of getting the function (code) to be called. It is easiest to imagine that the %code% blob is attached to the namespace of the object f, but, implementations might optimize this in different ways).

[Note that the syntax f.x (y) implies that f is passed as the this parameter, e.g. this becomes f.x.call (f, y). And, z (q) becomes global.z.call (z, q).]

In the case of new though,

var x = new YYY (...)

is converted to a several-step process

- temp = {}

- temp.%proto% = YYY.%proto%

- temp2 = YYY.%own%.%code%.call (temp, …)

- var x = temp2

In JavaScript syntax, this is passed as an implicit parameter to every function.

If a function does not execute a return statement, the function returns undefined, but, the function can mutate the this parameter.

A Constructor is a just a normal function that returns undefined. When called, though, a constructor function is expected to modify the this parameter. In essence, the compiler hard-wires an extra parameter into every function call and hard-wires the parameter name to always be this, i.e. the syntax

function f (x, y) { ... }

is macro-expanded to be

%callable% f (this, x, y) { ... }

The above only matters to compiler-writers. For everyone else, the documentation contains hand-waving references to functions and constructors. From a compiler-perspective, functions and constructors are the same. The compiler doesn’t need to remember which functions are Constructors, it simply treats all function calls as method calls and calls functions differently in the two cases (1. normal, and, 2. new).

Relationship to Lisp

JavaScript function names aren’t simple pointers-to-code, but are pointers-to-objects.

The objects can be walked to find code.

This is very Lisp-y.

In Lisp, functions are always anonymous (signified by the keyword lambda).

In Lisp every symbol (a symbol is just a name, a “handle”) contains a set of attibutes. One of the attribute values might be a lambda.

In Lisp1, it is possible to have a symbol that has more than one kind of value, e.g. a symbol might contain a datum attribute plus a lambda attribute.

Diagram

Code Transformation

function f (x) {

return 1;

}

is converted to

%callable% f (this, x) {

return 1;

return undefined;

}

(The second return is never reached, so the above function never actually returns undefined).

Call Syntax Transformation

There are several ways to call functions:

y.f(3);

and

var x = new f(3);

and

y.f.call (y, 3);

[In the following, I use % like a normal character, like JavaScript uses the _ character].

The first version is converted to

f.%own%.%code%.call(y, 3);

and, the second version is converted to

var %temp% = {};

%temp%.%proto%=f.%proto%;

%temp%.%own%=null;

var %temp2% = f.%own%.%code%.call(%temp%,3);

var x = %temp2%;

Stuff I Haven’t Figured Out Yet

Somewhere, JavaScript stores the name of the object’s type. I would guess that this is saved in the object’s prototype, but I haven’t figured this out yet.

When you call console.log (...object...), JavaScript tries to print the type name of the object. In the case of {}, it prints nothing as the type name.

See Also

Table of Contents

Blog

Videos

References

Books

-

In Lisp2, to be exact. Lisp1s don’t allow multiple values for symbols. ↩